Chris Bangle Talks Change at BMW, Life in Italy and What the Future Holds.

“It’s easier for people to make decisions about what they don’t like,” says Chris Bangle. “So you really have to spend some time explaining to them why they don’t like it.”

Bangle is sitting in the hills above Northern Italy, a compound of sorts he converted from an old farmhouse in, Clavesana, a small village on the outskirts of Turin. Far from the towering offices of Munich, Bangle likes this place, the Borgata; he says, "because it’s so weird,” “people who come here, are by the sheer nature of the place, not at home, so they know everything is a little bit different, it helps.”

Chris Bangle has his fingerprints on some of the most recognizable cars ever to come out of Munich. And 14 years since announcing his departure from both the car industry and BMW, it’s arguable that his influence is more visible now than it ever was.

Under his reign as the company's Design Director, Bangle became one of the most talked-about designers in automotive history. The radical transformation of BMW's styling language, from staid yet successful to an industry-changing phenomenon, catapulted him to levels of media attention few designers have ever experienced.

Once famously proclaiming, "We aren't copying anyone else's design language, not even our own!"

Bangle's mentaility stood in stark contrast to the approach BMW had subscribed to in the past. Recounting a story about his boss at the time, Dr. Reitzle, further highlights this shift in perspective. “A long-serving, very young, very personable, very telegenic manager,” Bangle says of Reitzle, “he was absolutely convinced on a particular design style. Underlining it with phrases to the press, like, ‘We know our style; we don’t have to define a new one. We know what we are.’”

“Which all sounds good,” says Bangle, “but where’s this gonna go?”

And it’s this simple question that seems to have landed him the job at BMW. Bangle’s hiring as the company’s first American Design Director was unexpected. But then again, so was the situation at BMW.

By 1992, the company had gone two years without a Design Director — a gap which Bangle characterizes as “really painful.” Noting that despite Dr. Reitzle’s beliefs, BMW had no reason to change, not all at the company shared this view.

Chris Bangle

"We aren't copying anyone else's design language, not even our own!"

“At that time, there was an expectation in the wings of the board of directors that this situation will not last,” Bangle says. It was an expectation shared by many at BMW, a sense that despite the company’s successes, BMW needed to change. But surprisingly, not a sense that Bangle necessarily arrived with. “I was not here to change this company,” he says, “I was there to learn, but the more I learned, the more I realized everyone wanted to change; they didn’t want to be on that track. They wanted to be somewhere else, but they didn’t have a way to express it.”

Bangle paints a picture of a somewhat divided BMW “You had people who, on the one hand, say we’re convinced of what we are no need to change anything, just adapt it.” He says, “But then you have this other view, which is, I want to see where we’re going,” “let’s decide on how far downstream we can we can pick, and then we run to it!”

“And it’s just a different vision for what the company is,” he adds. “But I was a layer underneath that. And so politically, not at all on those kinds of exchanges, but still, the expectations always come to us [the designers] to lead that vision.”

It’s a vision that did not realize itself immediately. Bangle, then 36, entered the company two years after the sudden departure of his predecessor Claus Luthe. This awkward gap in management meant that Bangle was inheriting a design program with its roots firmly in the late 80s — it wouldn’t be until the 2001 7 Series ended its six-year model run that the last car designed under Luthe’s management would leave showroom floors.

Bangle’s first ground-up project began development in 1993; the fourth-generation BMW 3 Series — dubbed ‘E46’ internally, it came at a pivotal moment in BMW’s history — a new CEO in the form of Prof Joachim Milberg meant Bangle had a management team which, according to him, felt “a sense of a need to move forward.” And BMW’s acquisition of the Rover Group meant the company was venturing into new markets with models such as the X5.

“Reasonable,” Bangle calls the X5 — it was perhaps the last vehicle produced by BMW still influenced by Luthe’s design language. He notes, “It’s a lot of credit to Chris Chapman and the design team that they managed to make it into the first real, upscale SUV.” And as a new model line for the company, the X5 needed to remain instantly recognizable as a BMW — resembling “a kind of blown up giant. Three, Five series wagon.” Says Bangle in a complementary manner.

The X5 was a sign of things to come. Bangle recalls that during this time, one of the biggest challenges the design team faced was that with each consecutive generation, engine heights relative to the rest of the car had to increase by a few inches. Anyone familiar with car design realizes the domino effect this instigates, raising all parts of the vehicle along with the engine, meant that after just a few generations, the design language that BMW had relied on for so many decades was quite literally at a breaking point.

“The engineers, though,” says Bangle, “always thought the last design we did was perfect, so why shouldn’t it be the same all over again?” “So what we [designers] usually did was we took the old design from the existing car, and we put it on the new package and showed what it would look like in those proportions. And that usually made everybody ill because it looks like crap.” “So they decided, okay, either we have to go back into the proportions in the package, or we accept the fact that you need a new design language to deal with this, which is basically when we did the radical stuff, how we got away with it.”

When Bangle came to the board with this same realization, he was essentially selling them on a new direction for the company; it was clear that this path would mean buying into an expensive design program. It wasn’t just the price of a new 7 Series, but the price of the new 5, the new 3, etc... as Bangle put it, “to show what would happen if we really changed things.” He says that if you can convince people that what you’re doing is really in their interests, you have a much better chance than by “going in with this mega ego and just, you know, intimidating the living shit out of everybody.”

Bangle is quick to compliment BMW in this regard, “it’s a top-down company,” he says, “when they make a decision, they don’t backtrack.” But at the same time, it’s a company with a long-term game plan; they expect problems to be identified early and solutions proposed. He recalls that the CEO, Joachim Milberg, would come to him and say, “Don’t show me the next car, show me the next, next, and then I’ll understand why the next is what it is.” Bangle says, “When you show [the board] this is going to be a design format for our future, they want to know what comes after.” It was not enough to design the next generation of cars. Bangle and his team had to show what the multi-generational consequences of their current work meant BMW would have to commit to in the future.

Chris Bangle

“Either we have to go back into the proportions in the package, or we accept the fact that you need a new design language to deal with this, which is basically when we did the radical stuff, how we got away with it.”

It is largely in this regard that Bangle’s legacy continues to be felt today. The multi-generational consequences that he and Milberg discussed in the late-90s is the modern-day automotive world we currently live in. Walking into any design studio is like looking through a lens into the future. It’s by the sheer length of automotive development cycles that it may take three-quarters of a decade for a car to go from pencil to production, but in Bangle’s case — that lens had to be more than doubled. Developing a design strategy that looked generations into the future forced the 1996 design team to lay groundwork for cars that would be hitting showroom floors into the 2010s.

“[it] was all about multiple generation consequences of this [work],” says Bangle. He showed the board how his newly proposed design language turned a problem — increasing engine heights — into an opportunity for a new design format that could push the company’s products further. The board approved it, and by September 2001, The E65 7 Series, as it was dubbed internally, succeeded the well-regarded but conservatively-styled E38 model.

When the E65 went on sale in 2002, critics were impressed by the new 7’s engineering prowess but confused by the sudden departure in styling and the addition of iDrive, which even Bangle himself admits, BMW probably shipped “far too early” for its level of technical maturity.

The shock of the E65 thrust Bangle into the public eye. Even at the time, many people recognized the revolutionary nature of the work BMW was doing, but a violent few did not. The term ‘Bangle Butt’ was quickly coined in reference to the 7 Series’ raised trunk line, but largely by people who had never seen the car in person.

Bangle himself is the first to admit that his cars suffer in photos. During a Car and Driver interview, he said that “If, for instance, you’d never seen, then suddenly saw only a side view of the car, well, it suffers,” in reference to the E65 7 Series, “one of the most unusually proportioned vehicles ever.” He says. “For complex cars, you need to take that ‘memory walk’ 360 degrees around the car, and then you see how the different themes are connected.”

Bangle says that product lines follow a cycle of revolutionary generation followed by an evolutionary generation and another revolutionary generation. He believes it was a polarizing effect needed for BMW at that time. And it seems customers agreed; the 2002 7 Series sold 4,000 more units in its first year than any Seven before or since, with 22,000 vehicles delivered in the U.S. alone. The car was an unquestioned business success and, over the years, has become well-regarded as far ahead of its time.

“Design is the engine of the train,” says Bangle, “when everybody else is partying in the back of the train, saying, oh, look at the sales we’re having right now! We’re the first ones into the tunnel going; we’re going to be screwed. Because the packages are doing this to our cars, everything you love about them, you’re not going to have in the next generation. And then, while the rest of the train is in the tunnel, screaming and moaning, we’re the first ones in the light coming out of it saying, hey, no, and guys, don’t worry, it’ll work. We got it, you know?”

Prof Joachim Milberg — CEO, BMW

“Don’t show me the next car, show me the next, next.”

And he did have it; by 2004, Bangle was BMW’s Group Design Director when the all-new Rolls Royce Phantom VII was released. BMW controlled both Mini and Rolls, with the three marques being distinctively different; you’d expect Bangle to keep the trio intensely separate, but no. “The more you keep them separate,” he says, “the more they come up with the same solutions, and they think it’s there’s. You have to put them into the same room, physical space, where they can see it being developed, they can see Rolls Royce becoming its own self, they can see Mini becoming itself, they can see the motorcycles and the cars, adding their own bits of famous DNA to each other, and at the same time maintaining their own individuality.”

“I hate this word about DNA and cars,” Bangle adds scoldingly. “Because the difference between men and women is like, it’s like 12% DNA. And the difference between a man and a monkey is like 8%. So like, I always ask people what kind of what is the DNA you’re talking about?” “Is it the 8% that keeps us away from being a monkey?!?”

At Chris Bangle Associates — the Italian based design consultancy that Bangle founded after leaving the auto industry in 2009 there are no monkeys, and the offices are tiny compared to BMW’s Munich skyscraper but far more inviting — called a Borgata (the Italian word for a type of house collective that is too small to be a village but more than what would belong to a single farm). The area consists of just four buildings placed atop the Italian hills in an almost deliberate oasis away from the harshness of the modern auto industry.

Upon leaving BMW, the company asked Bangle not to re-enter car design for several years. He happily obliged, saying today that the projects at CBA are incredibly varied; working alongside his family and a small team of mostly Italian designers, anything goes, from a charming animated short, ‘Sheara,’ to V.S.O.P. Cognac bottles and Bangle’s only automotive project since BMW, a small electric city car called ‘REDS.’

Revolutionary Electric Dream Space, REDS, Bangle proclaims proudly, is “a car that is at its best when it’s parked.” It came about, he says, when ‘China Hi-Tech Group Corporation’ asked him to design a small car for their new company. Bangle initially balked at the idea and asked them why they wouldn’t “go up the street” to Pininfarina? “They’d love to do that for you,” he said in an Autoweek interview.

When the company insisted on Bangle, he cautioned them, “‘If you are going to go about it in a normal way, you are going to end up with the exact same kind of a piece that everyone else does, and I really don’t want to do that.”

Bangle wanted a car that would “invert the relationship between the vehicle’s looks and what it does with our general understanding of the automobile.” Spending two years working on a concept that, according to him, had no real aesthetic concerns whatsoever. Relaying a story in Automobile where one of his designers said, “‘I can’t do this,’ and he got sick, literally sick. He came down with a bad flu, and he spent three days in his hotel room, eating soup - and drawing what I had asked him to draw. And when he came out, he had created something no one had ever seen, and he said to me, ‘I am liberated.’” (Quote from Autoweek)

Bangle is keen to explain that “we previously understood cars that go between A and B, and therefore they have to look like they go between A and B, they have to look aerodynamic, they have to look all these things, right? REDS was designed for a mega city, China, where cars are not moving like 90% of the time.”

It’s in that 90% when the car “is at A and at B,” says Bangle, where REDS will have “superior performance.” It’s the sort of thing that he believes will differentiate electric cars in the future. “Once we embrace the 90% of the time the car is not moving, [you] realize that could be the real added value,” Bangle says, “you can use it, you can sit in it, you can do all kinds of things in it.” For the 10% of time, the car is in motion, all four seats face forward, but it’s in the 90% where you can flip around the driver’s seat to “create a face-to-face environment.”

In large cities, he says, where privacy can often feel like a distant impossibility, REDS focuses on giving people a private environment to use as they see fit. Young entrepreneurs, says Bangle, could utilize REDS’ flexible interior space as a private office or as a place to relax.

Bangle’s vision differs from that of companies who prefer autonomy as a potential ‘solution’ to this problem, assuming that customers will want to let their vehicles loose on a driverless Uber-like service. Bangle says he does not necessarily “see a future of nondriving non-driver drivable vehicles as being a bad thing; it’s almost inevitable.” But he does not believe that “people’s desire to want to drive and get the most out of a car personally as being a bad thing, either.”

Being quick to remark, “People like to think that the secret of the Automobile was that it provided people with a quote-unquote, freedom. But actually, I don’t believe that’s true.” “What the automobile provided was the ability for you to set your own pace.” He says people had horses and bicycles, which gave them freedom, but with “a car, you can actually get there ahead of everybody if you wanted to.”

“And if you look at the whole history of automotive legislation,” Bangle says, chuckling, it’s basically been to try and curb that one freedom.” He’s interrupted briefly by his wife, handing him an espresso, “Oh thanks darling, coffee’s arrived, thank you,” he says jovially — continuing, “electric cars seem to have this mono-dimensional idea performance in their head of acceleration, it’s Okay” He says demurely. “I mean, good, you’re accelerating. Everybody in the car threw up, you know; what the fuck?” He says accusingly. “I don’t really get into that that much.” Adding though, “I think in general, the driving experience per se, will change in its in its importance for the car,” Saying that so long as you want to drive cars, the experience of interacting with them will continue to be important, “but if your vision for the car is not something you drive, and half the time, you’re not the one controlling it you might as well experience something else.”

Special thanks to Chris Bangle for participating in this interview, for more information on his latest projects visit: chrisbangleassociates.com

Continue Reading

Braun Travel Alarm Clock - A Charming Palate Cleanser.

There's something immeasurably charming about a little thing done right. So often, it seems that such things are unutterably expensive, but I think one of the greatest failures of modern design is that consumers have been led to believe that "design" just means "expensive."

But this little Braun Alarm Clock is a pleasant reminder that this is not the case. At just $19, it’s hardly expensive and is yet, somehow, inexplicably charming. I bought it last week for no seeming reason other than I wanted to. It's a very familiar looking-thing, mainly because its been around since the early 70s, and at under $20 struck me as a great way to finally own a vintage Braun product.

Design

Upon first glance, the Travel Alarm Clock is everything Braun Design under Dieter Rams should stand for. Its shape is the proverbial rounded rectangle, though now standard in Industrial Design, it was first popularized by Braun and later Apple.

But where this design shines is in its balance, visual balance, that is. People often wonder why Braun Designs of this era look somehow perfect, and it’s because of that balance.

The result is that nothing tugs at your eyes; nothing overwhelms you. It goes back to the famous Leonardo da Vinci quote, "Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication." People often like using this line because, it's an easy justification for excusing under-developed design as "simple." But looking closely at the Travel Alarm Clock, one can't help but admire the level of work that went into achieving said simplicity.

Everything is in absolutely perfect visual and mental proportion. Starting even with the shape itself, though a rounded rectangle, there's so much more than meets the eye. Looking at it on a desk, it appears to be a perfectly extruded shape. But look at it from the side, and immediately you'll notice slight tapers front and back.

It's a visual trick; humans don't perceive perfect cubes accurately. And by tapering the edges, Braun gives the impression of a far lighter, less imposing object. And when viewed from an angle, say on a desk or nightstand, the clock appears far more natural and planted. With a slight part line, giving a nice visual break from the main body to the clock face.

Speaking of the clock itself. The front face is classic Braun, instantly identifiable, and incredibly readable - once again, a triumph of visual hierarchy. Your attention is immediately grabbed by the dial, which, perfectly recessed into the body, tells you everything you need to know. Nothing more, nothing less.

There's no gratuitous use of color, nor is the Braun logo front and center like in so many other products today. The simple uses of contrast and a slight splash of yellow on the second hand are delightfully understated and incredibly honest.

Function

Operationally, the Travel Alarm Clock is incredibly straightforward, just a basic quartz movement, with alarm and clock-setting functions at the rear.

Despite its simplicity, though, this is one area where technology has spoiled us. A week in, I still need to get used to the old style of setting the alarm. The rear dials, though well-explained, remain confusing and at times infuriating to use, I'm sure that with time I'd get used to it, but, I'd still hope for a slightly more intuitive experience.

Not remotely infuriating, though, is the alarm on/off selector. It pops in and out of the top body with delightful satisfaction, and the small green dot delineating its function is once again a tremendous use of color.

When up, in its on position, that same green color is visible on the front of the now-revealed switch, with a corresponding hand on the clock face also sporting a slight splash of that same green.

Similarly charming is the night-lite function, which the push of a button on the top right can activate. It's noted with faint grey text: "snooze/light," and although it's nothing special, pressing that button casts a warm glow on the dial - just bright enough to read at night without irritating your eyes.

Initially, it seemed surprising to me that Braun opted for a non-uniform light source to illuminate the dial. But having spent some time with the clock on my desk, I have to say that the slightly off-canter lamp makes for a charming effect. Though technically inferior, the almost sun-like glow adds dimensionality to the dial, especially at night, making it appear quite friendly and inviting.

But there's no denying the Travel Alarm Clock is fundamentally an outdated product; there's nothing it does that my phone can't. But its charm lies in that technical irrelevance, and In a world of increasingly complex and convoluted design, it serves almost as a pallet cleaner. One that's unobtrusive, functional, and incredibly pleasant to live with.

Continue Reading

The iPhone Changed Our World. It’s Also Making Us Forget What’s Real and What Isn’t

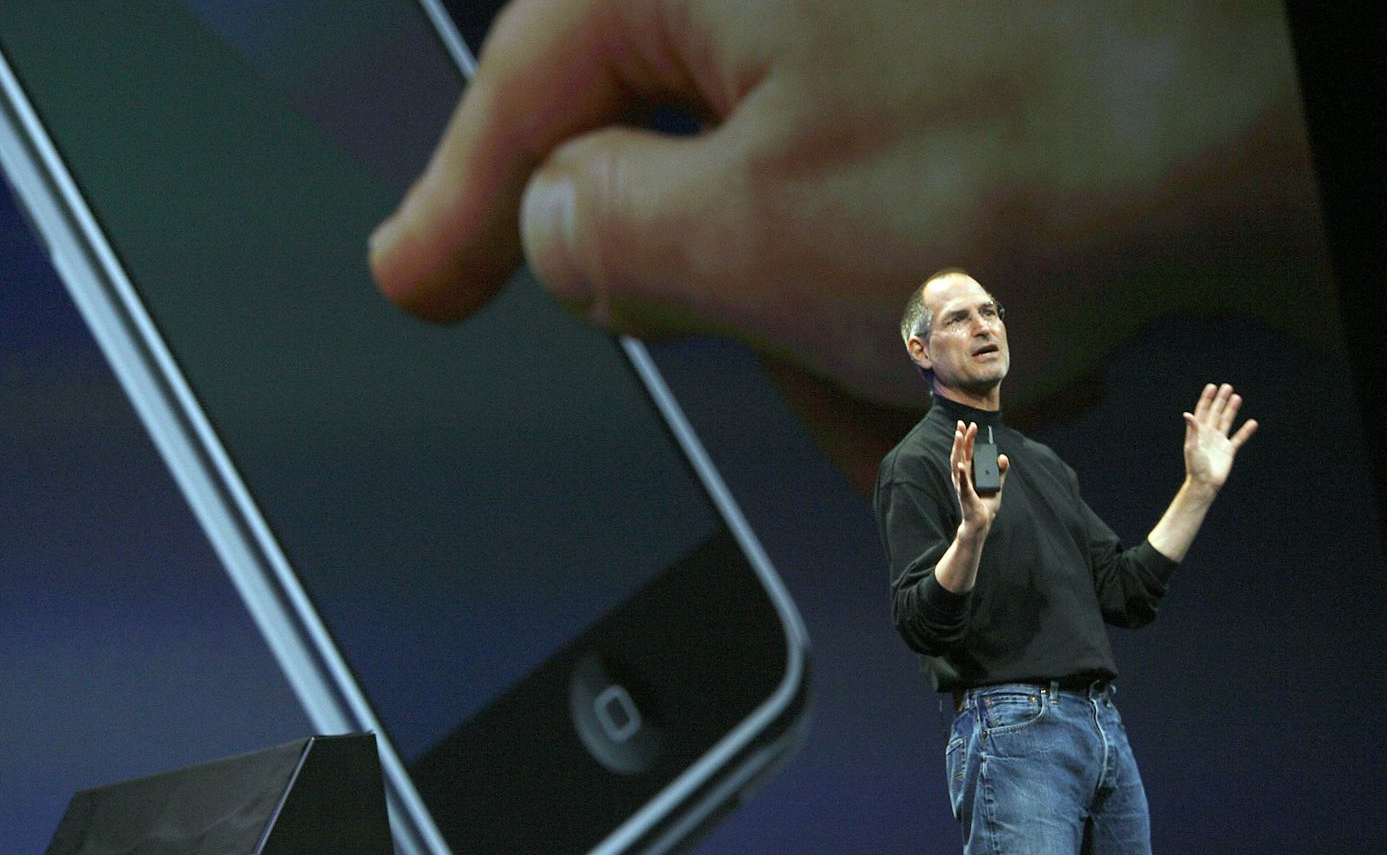

In 2007 when Apple first introduced the iPhone, few could have imagined the transformative effect this device would have on our society. Sixteen years later its success is undeniable, but have the things it enabled blurred the lines between what’s real and what isn’t?

Before writing this article, I watched Steve Jobs' introduction of the first iPhone. It was a masterful presentation, one of his best. Jobs opens by saying "Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything." Decades later, it's safe to say he was right.

But even then, there was a palpable sense that what Apple had introduced would be a big deal. It's important to note that at the time, in 2006, the iPod alone represented 40% of Apple's revenue; naturally, the company was concerned about what would threaten it. And by the early 2000s, it had become clear that mobile phones, with increasing storage and computing abilities, would soon be able to offer built-in music players that would heavily reduce the appeal of a $499 iPod.

The iPhone, in many ways, was born out of a need to pre-empt the iPod's eventual obsolescence. Existing "smartphones" of the time were clunky and underpowered, but collectively they had many of the core functionalities that the iPhone would soon adopt. Email, texting, internet, calendars, and music, the iPhone was not the first to bring any of these to the market.

The iPhone's true innovation was how it delivered these functionalities. In 2006, phones were a jumbled mess of plastic keyboards and tiny, underpowered screens; manufacturers were trying to cram desktop UIs into a mobile hardware-software mashup that just didn't work. The iPhone was different- it leveraged a technology called multi-touch that allowed for unprecedented flexibility. Though initially intended for the iPad, this technology was so compelling that Apple paused development to use multi-touch for a phone instead. A risky choice that could've doomed the project but one that gave the iPhone its identity.

Multi-touch freed the iPhone from the shackles of a hardware keyboard, overnight giving the device 50% more screen real-estate that Apple could use for whatever they wanted.

The App Store

It may surprise some to learn that the first iPhone did not ship with any form of App Store. It wasn't until the iPhone 3G in 2008 that Apple finally allowed third-party developers to run apps natively on the device. The Store launched with just 500 apps and a charming commercial with the tagline "There's an App for that."

Looking back at it now, the ad seems almost innocent in its attitude toward what the iPhone would eventually amount to as a software platform. These days there are literal millions of apps on the iPhone, but back in 2007, the iPhone was, first and foremost, a tool. Multi-touch was merely a vehicle to make familiar features easier, more powerful, and, crucially, more intuitive.

With the App Store and the advent of 3G, the iPhone suddenly became much more than a phone. The apps that ran on it took the magical new u.x. interface that was multi-touch and ran with it. By Christmas of 2008, one developer had made a million dollars, and by the end of 2009 over 100,000 apps had made their way to the iPhone.

And as the iPhone's computing, photography and cellular capabilities advanced so did the apps that ran on it.

Digital vs. Physical

Apps quickly became an easy way to replace physical activities with virtual replacements. The appeal is understandable; most apps on your phone make once time-consuming activities instantaneous and infinitely convenient. Some of this is good. Banking apps, email, health tracking, calendars, weather, etc… all are examples of technology making our lives better by reducing wasted time. These apps don't so much replace physical interactions but rather empower us with new tools that would otherwise be non-existent.

The problem comes when apps begin replacing once physical experiences with virtual substitutes that may be more convenient but are not necessarily better. This may seem obvious in a post-Covid world, but just as an ad once said, "There's an app for that," there truly is. But instead, now, it's no longer parking and food tracking but dating, socializing, and work.

This creates a paradigm in which companies have convinced us that instead of going out and interacting with people, "There's an app for that!" But these things, they're not quite full-fat. Virtual social lives, virtual dating, virtual work, this is not how humans interact. Humans do not socialize through even the best fiber-optic lines - it’s not real, there's no energy.

Still, some say the virtual world is better, more convenient. But having lived the virtual world over, and over, and over again. With all due respect, Are .. You .. Kidding .. Me?!

You ever wonder why people still get together? I often wonder why in this age of Instagram, people are still willing to go through the pain of making plans, keeping arrangements, and physically seeing each other? We have this incredible technology; why don't we all just stick to our devices; it's so much easier because it isn't real! That's why.

At the end of the day, you cannot, will not replace real tangible things with digital substitutes. It's not natural; it's not human.

Productivity, efficiency, convenience, these are not words that stir the human spirit. I hope we snap out of this cycle soon because I don't know about you, but I'm not ready to live in a virtual reality.

Continue Reading

2018 Morgan Three Wheeler; Sometimes The Old Ways Are Best.

There's a scene from "Gone in 60 Seconds" in which Nicholas Cage complains to his Ferrari dealer that "There are "too many self-Indulgent wieners in this city [L.A.]" Continuing,

"Now, if I was driving a 1967 275 GTB four-cam…"

Roger the Car Salesman:

"You would not be a self-indulgent wiener, sir... You'd be a connoisseur."

This line echoed across my head as I stood before the Morgan Three Wheeler. Cage was right; L.A. is filled to the brim with "self-indulgent wieners."

In his mind, a 1967 Ferrari was a ticket out of that club. Clearly, though, he had never seen a Morgan before; if he had, this would certainly have been his answer:

The car you see before you is a 2018 Morgan Three Wheeler, that's right, 2018, not 1918 - it's made partially of wood and has no interest in what you think a car should be. For these reasons, I love it. And I'm not alone; other people love it. I've been in many cars, cheap cars, fast cars, slow cars, expensive cars, vintage cars, none get the level of positive attention this thing does.

At 3 miles an hour driving through sweltering traffic, with the Three Wheeler's engine obnoxiously thumping away, everyone smiles. Guys, girls, kids, grandparents, and the drug dealer across the street all love it. The number one question everyone asks is, "what year?" Most women just ask, but guys, for some reason, feel obliged to shout out a number; rarely did I hear any newer than 1965 - it was always with some degree of glee that I shouted back, "2018!" The shocked looks on their faces were always apparent as the Morgan's single rear wheel screeched away from a light.

But the Three Wheeler is no retro throwback.

Morgans have been built in the same way, in the same place, since the very beginning. Most car companies will do a complete clean-sheet redesign of their model line at least once a decade, but not Morgan. The general rarity of many ground-up redesigns results in styling that places Morgan firmly in the mid-20th Century but with powertrains and customers that have kept up with modern times.

Most new Morgans built today come with either Ford or BMW motors, so rarely does one feel that they are lacking for horsepower. Even on paper, the outgoing Three-Wheeler I drove can match most modern cars in acceleration - and while a 0-60 time of 6.0 seconds hardly seems overly impressive, you'd be forgiven for mistaking that number for 0.6 seconds.

Most modern sports cars deliver power with such competence and efficiency that automakers often feel the need to pump sensation back into the cabin through speakers and carefully tuned exhausts. It's a sad fact, but in just about any modern sports car I've driven, the speed becomes very dull very fast, so all you're left to do is ponder which one you'll buy next.

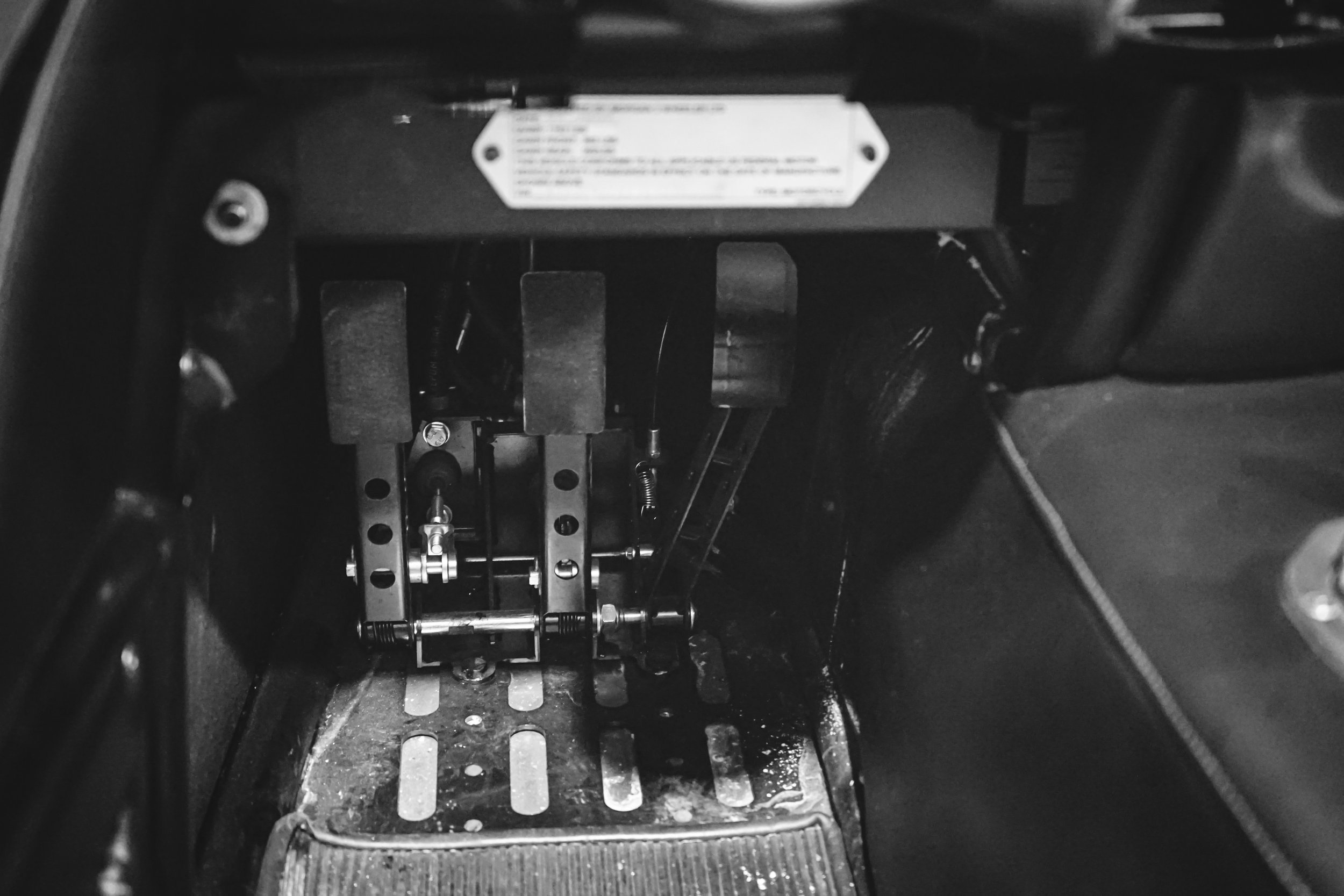

In the Morgan though, this is hardly a problem. Put your foot down and suddenly the whole world erupts into a firestorm of noise, vibration, and acceleration. First gear, second gear, third gear, surely one must be doing at least 150 mph by now, but no… I haven't even broken the speed limit. The Three Wheeler is an attack on all the senses, add microscopic windshields, thundering exhausts, an aircraft-like driving position, and the Morgan makes for a truly hilarious driving experience.

And that's all before you remember that the car you're in has all the safety and structural properties of a road-going canoe. And while that is something of an overstatement, it's a common trope to claim that Morgan cars are made of wood. In the Three Wheeler's case, though, ash wood is used to secure hand-beat aluminum panels to a steel chassis - but don't get me wrong, this car is hardly cutting-edge.

When driving the Three Wheeler, there exist fleeting moments of clarity in which one understands the sheer absurdity of the activity they're engaging in. Morgans do not have most of the safety and technological features we've become accustomed to in modern cars. Crumple zones? Roofs? Radar Cruise Control? Airbags? Functional Windshields? Nah, the Morgan doesn't bother with any of that - but what would ordinarily send buyers fleeing gives the Three Wheeler its competitive edge.

We're so used to fake fear, fake speed, fake noise, fake danger, that it's incredibly refreshing to drive something that ignores all of that in favor of real fear and real danger. That's right, the Morgan is an honest car. Sure, there are quite a number of vehicles on the market today that can scare the absolute crap out of you, but in most, there's a feeling that the roughly 10,000 computers on board will be there to catch you.

Not so in the Morgan. The sheer unbridled danger of it all only serves to enhance the experience; this is a driver's car in the truest sense of the word. To get the most out of it, one needs the perfect blend of skill, experience, and self-delusion to push the limits. I'm not that person, which means that every time I drove the Three Wheeler, I was forever finding new boundaries to probe.

And for that, I love it.

Last of its kind.

It's important to note, I think, that Morgan exists today for seemingly no practical reason other than fun. They make products the likes of which we haven't seen for decades, things you can't get anywhere else, a sound business model if you ask me. But crucially, Morgans are incredibly magnetic products and possess the most important of qualities - soul.

They do this through incredible purity of purpose, something most cars struggle with. Purity of purpose can be anything. If your goal is to make the world's fastest car, and you succeed at it, that car has an inherent honesty and is something you can bond with. The same is true for all Morgans, though perhaps slightly harder to pin down; few come away from driving a Three Wheeler without at least once exclaiming, "This is the best car in the world!"

Morgans are cars you drive just for the sheer unbelievable fun of it all, and to hell with what everyone else is doing.

That's the spirit of a Morgan, and because it is so literally handmade you get a sense of the people who made it. Whether it be the hand-sewn upholstery or perhaps the Eurofighter bomb-release switch that acts as the car's starter. At no point while driving one of these cars, does one lose a sense of the people who made it come to life and, most importantly, their values.

Jonathan Wells.

I had the great pleasure of speaking with Jonathan Wells, Morgan's head of design, only the second ever in the company's 113-year history.

Jon faces challenges, not unlike the rest of the industry. As regulations evolve, so do the cars these regulations govern. But unlike most designers whose brands revolve around modernization, Jon faces a philosophical conundrum: Suppose your company has spent the past century cultivating an image as the world's last purveyor of classic British sports cars. What happens when the British sports car as we know it becomes outlawed?

Jon's immediate response was a quote from Soichiro Honda, "In the future, there will be just half a dozen car companies…and Morgan."

I'd heard this line a few times before, but to hear it coming from Morgan's head of design made it all the more amusing.

Jon followed up, though, with a fascinating perspective, one that lends itself to what a British sports car, a Morgan, truly is.

"I think at Morgan, we always have to tread a very fine line between tradition and modern. In the U.K., we would refer to some cars as being wedding cars, whereby they look classic and traditional, but underneath, they're sitting on top of a Ford Focus. And Morgan need to avoid becoming that; we need to celebrate the best bits of our past but also embrace the future."

"It's also not until you get closer. And see the way we're still coachbuilding, meet the craftsmen at the factory still hammering aluminum into shape." "You go, Wow, this isn't an ordinary motorcar. You then start seeing some of the engineering and the technology and performance figures, and you go, Crikey. I think our biggest challenge in bringing some of those messages to the mass public was such a small marketing budget, and I think we've also got a great deal of flexibility to challenge perceptions going forward. So it's a really exciting time for the business."

A New Direction.

Morgan's latest product, the Super 3, is an all-new replacement for the Three Wheeler. It is both a product of its times and also a sign that the old ways of doing things aren't going anywhere.

In regards to the Super 3, Jon highlights that "it is quite a departure from the previous product language."

"Obviously, on the old Three Wheeler, its predecessor, the engine was doing a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of the styling. And now it is much more about the body and the aesthetic."

"For us, it was important, the Super Three wasn't a retro homage, but instead, it's sampled bits of the past and rearranged them in a way that is new." "A lot of parts of the vehicle are inspired by early fuselage manufacturing techniques where two halves of the fuselage would be bolted around the seam. The whole aesthetic of the tail takes influence from the early three-wheelers."

"There's lots of mid-century influences in some of the switch gear and the dials and some of the typography and graphics on the clocks. And what we're essentially doing is sampling the best bits of past decades and rearranging them in a way in which it looks new. So we're still looking backwards in many ways."

The Future.

Sensing perhaps, though, that not all of Morgan's customers are ready to abandon the traditional aesthetic the company is known for, Jon outlined Morgan's product strategy for the foreseeable future.

It's a strange thing, really; as our digital devices become more and more convenient, "Super three, for us, represents more than just a new Three Wheeler. 'Super,' the nameplate, the nomenclature of 'Super' actually represents a new product line for us as well."

"So whereby we have the 'Plus' product line with the Plus Four and the Plus Six. They sort of take inspiration from the early century. They're quite romantic in their styling approach. Still very honest. There still is a running board which is also a wheel arch. There still is a wooden frame that is the tool for hand-beating aluminum as well as carrying the leather. It's still very honest. But definitely take inspiration from the romance of the early century."

"'Super' is much more about technical functionality; the honesty in Super Three comes from the technical constraints influencing the design. So it gives us opportunity to introduce future vehicles carrying the super nameplate that may not have three wheels. So we could have a Plus Four, a Plus Six, maybe there's a Plus Three with three wheels. And on the flip side, we can have a Super Three and a super something else. So it's given us a new bloodline to play with as well. So the departure was intentional, in that sense."

This was exciting news, and having driven the now outgoing Three Wheeler, I am pleased to hear that Morgan has no intentions of abandoning its roots. Equally pleased, though, because if there were ever a time in automotive history when we needed the existence of such a company, it's now. This decade is one in which many automakers will find themselves in a battle to find their place. It is likely that many will not make it. To paraphrase Mr. Honda, at the end of time, there will be but four car companies… and Morgan. This creates an even greater imperative for companies such as Morgan, who have an unshaking understanding of what they do best, to continue creating the products they're known for.

I look forward to seeing what Jon and his team do next and am excited for when the latest batch of Morgan cars hit U.S. soil sometime next year, at which point we'll finally be able to take them for a spin.

Special thanks to Morgan head of design Jon Wells and Dennis Glavis, owner of Morgan West - Los Angeles

Continue Reading